Empire gown from Delineator, January 1893. Butterick pattern #4944.

Sometimes a new fashion takes off and becomes dominant. Sometimes not!

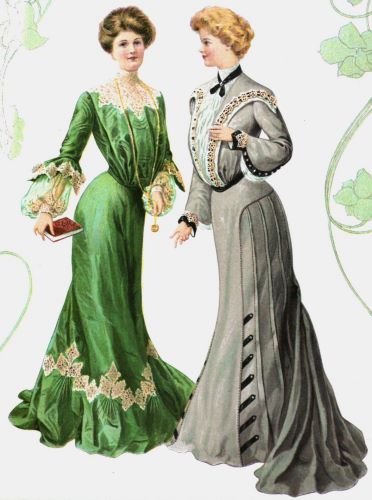

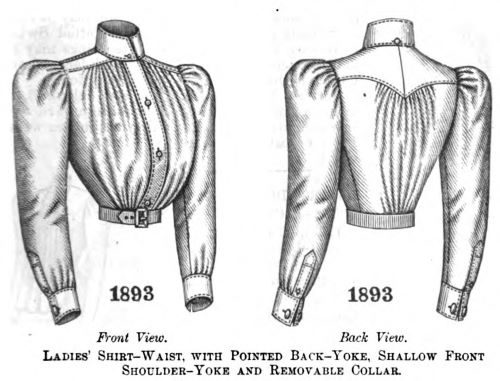

While browsing through a fashion and pattern magazine from 1893, I learned something new — which may interest vintage clothing collectors. This is a typical style from 1893:

A typical fashion from January 1893, Delineator. A tightly fitted bodice, with huge Leg-o-Mutton sleeves contrasting with a tiny waist.

The huge sleeves and very tiny waists that are associated with the mid-eighteen nineties were already The Fashion in January 1893.

But there was an attempt to introduce a return to the Empire style of 1805:

Empire style dress, early 1800s. Metropolitan Museum collection.

Short-Waist Empire pattern 4912, Butterick, June 1893. Delineator.

This attempt to to revive a fashion from early in the 19th century took me by surprise.

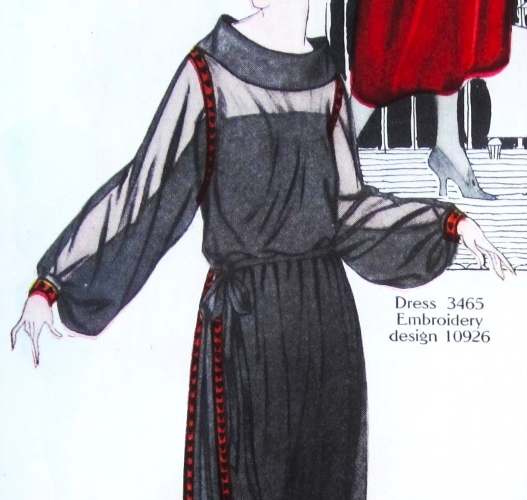

Butterick Empire Gown and short Empire Jacket for day wear, Delineator, January 1893. This dress has gathers in front and in back, like early French Empire gowns.

The high-waisted jacket of the Empire and Regency periods was called a “Spencer.”

A Spencer jacket. Early 1800s. Metropolitan museum.

This “Ladies’ Empire Jacket,” Butterick pattern 4934 from 1893, could be worn over other outfits.

Butterick Empire Jacket pattern 4934. Delineator, January 1893.

Another “bolero” length jacket was the sleeveless “Zouave Jacket,”

a revival of a style popular in the 1860s.

A sleeveless “Zouave” jacket from Butterick, Delineator, June 1893.

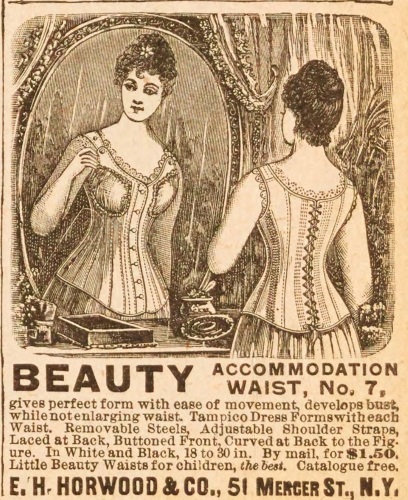

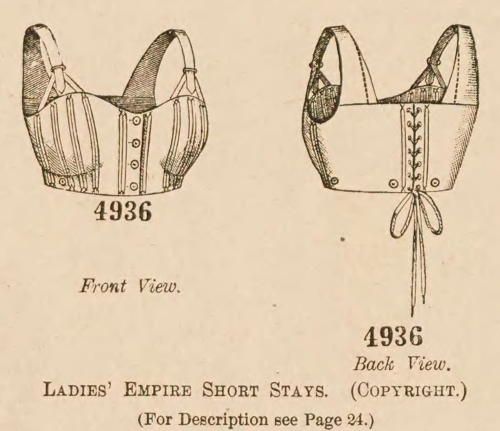

The 1893 Empire fashion required new undergarments, including new corsets that stopped inches above the natural waist.

“Empire Short Stays” were underwear designed to be worn under the new fashion. Butterick pattern 4936, January 1893, Delineator.

Notice the buttons, which were necessary to hold up the petticoat, since it would otherwise slide down to the natural waist.

Notice how this “Empire Petticoat” buttons on to the Empire Short Stays, or corset.

Just as happened in the early 1800s, the skirt part of the Empire gown evolved to have a relatively flat front, with most of the fullness pushed to the back.

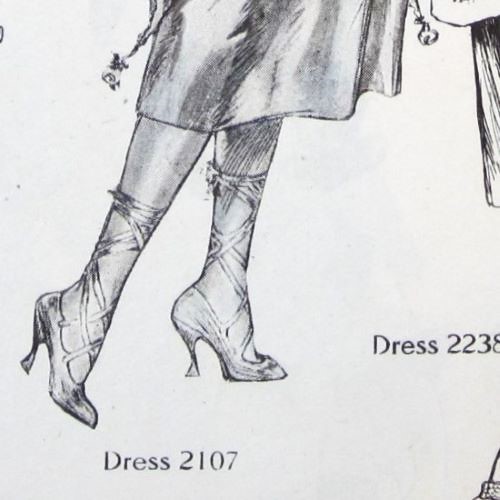

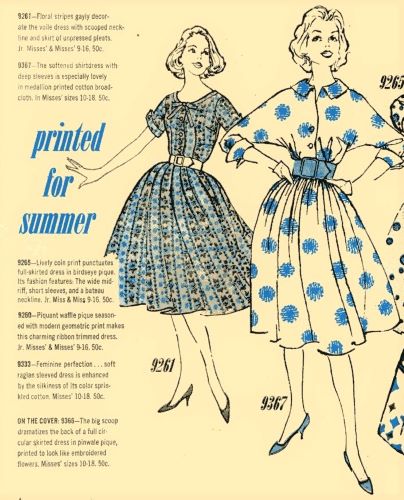

The “New Departure” in 1893 was the Empire Waist. Delineator, June 1893. Pattern 4971, lower right, has no gathers in front.

Very quickly, the term “Empire waist” stopped being restricted to gowns that would have looked familiar to Jane Austen. (“The Empire”was that of Napoleon. Here is a portrait of his Empress, Josephine. Her 1805 gown is slightly gathered at the front, with most of the fullness pushed to the back:)

Portrait of Josephine de Beauharnais by Robert Lefevre, c. 1805. Wikipedia

Some of the 1893 Empire gowns look more like Regency styles.

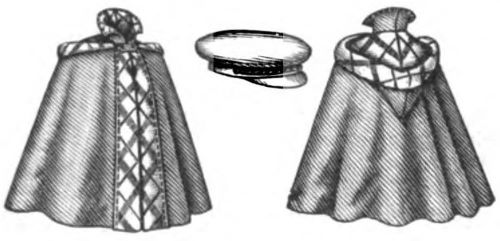

Alternate views of Butterick 4944, Delineator, January 1893.

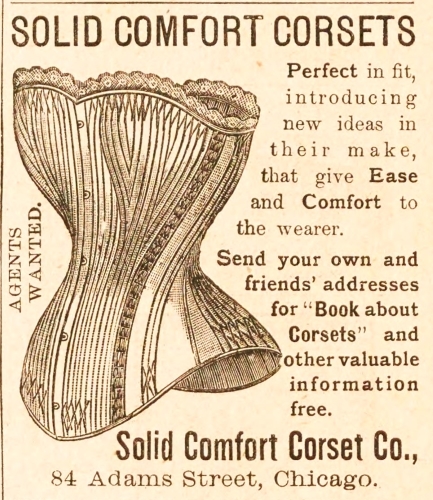

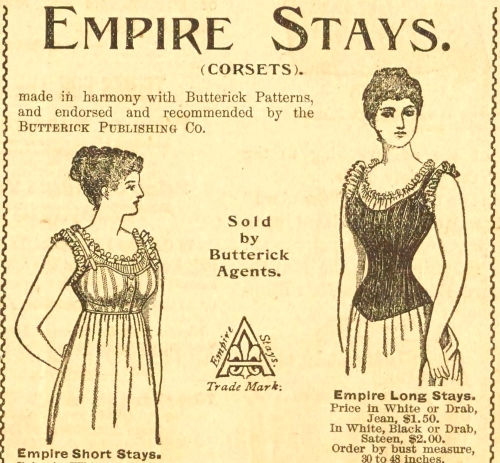

And Corset manufactures offered this:

“Empire Stays” could apply to a normal, long-waisted corset, as well as the short stays offered by Butterick. Ad, Delineator, June 1893.

What, one may ask, makes those long stays “Empire?” [Afterthought: I noticed that these are corded stays, rather than boned stays….]

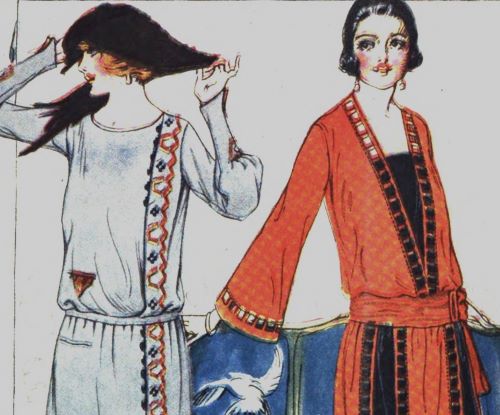

Well, instead of a short-waisted top with a full, gathered skirt attached, Butterick’s Delineator magazine began applying the word “Empire” to bodices that were tight to the normal waist, but which had a sash or fabric change a few inches below the bust:

“Ladies’ Empire Costume, with Removable Jacket,” Delineator, January 1893.

Here is an “Empire Belt:”

“Ladies’ Empire Belt” pattern 4923, Delineator, January 1893.

However Empire or Regency ladies would not have recognized these styles:

“Misses’ Empire Waist,” Butterick 6218, June 1893.

Misses’ Empire Waist” 6218, June 1893, Delineator.

“Ladies’ Empire Costume” with “Empire Circular Skirt” & “Empire Jacket.” Jacket pattern 6257, Delineator, June 1893.

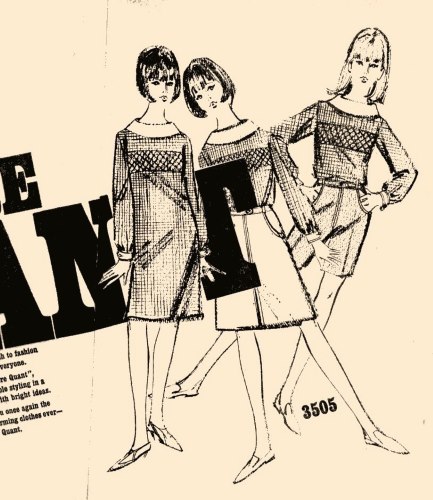

Fashion reporters began to call bodices with a natural waist line “the 1830 bodice” (and a full or circle skirt became the “1830 skirt.”)

I poked around in 1893 newspapers and found that the 1893 “Empire Waists” were definitely a topic of debate. [“Waist” was the 1893 term for a bodice, but in this case it also referred to a waistline just below the breasts.]

In March of 1893, The Miami Republican published “Styles of the Empire: Fashion Sailing Between Two Dangerous Rocks of Antiquated Designs. ”

‘You might as well wear a Mother Hubbard and be done with it,’ is what a man said to his wife the first time he saw her in full empire rig.”

A “Mother Hubbard” robe/wrapper/negligee, from Delineator, April 1899. Some men disliked the waistless, figure-hiding Empire garments; to some, the Empire gown was not suitable for public wear.

The newspaper conceded that “the empire frock is comfortable….” while “The 1830 waist, on the contrary, is quite long and very slim. So slim that our healthy young women groan and wonder what they could do, even if it were possible to squeeze into it, for they could never stay there.” But the comfort of the empire waist seemed too self-indulgent, suited to “the woman who would like to sit around in a wrapper [loose house robe] all day.”

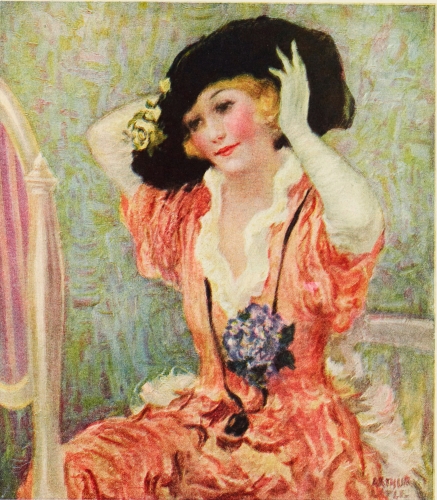

The St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 4, 1893, devoted several pages to a huge ball held in Missouri, describing what was worn by all the ladies — in alphabetical order. Mrs. Henry Allen wore a gown of green faille over an underdress of green, “empire waist outlined with a girdle of gold and green passementerie,” plus a gold comb in her hair. Miss Mary Breckenridge wore pink and white, with an empire waist. Miss Florence Bliss wore white China silk, her empire waist “trimmed with bands of red velvet.” Mrs. C. J. Dunnerman wore black and gold for her “empire waist with crocheted vest over gold satin.” Miss Bessie Davenport was all in white, with an empire waist, while Miss A.M. Douglas’ empire waist was cream silk, and Mrs. J.S. Finkenbiner’s gown was heliotrope bengaline, with an empire waist….

At least eight other ladies — out of more than a hundred — chose to wear the new empire gowns. But it was a minority choice.

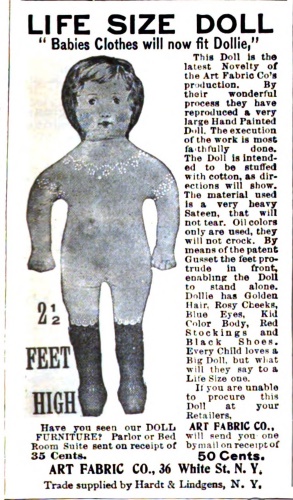

It might be tempting — if you find a high-waisted gown from 1893 or so — to classify it as a maternity garment. But not necessarily! Many of the ladies attending that ball in “empire” gowns were “Miss,” not “Mrs.”

Empire dress for Misses, Delineator, January 1893.

Garments called “Tea Gowns” or “Wrappers” often featured fullness over the midriff, but they also had an inner lining that was snugly fitted, like an ordinary bodice or dress. That was true of this vintage garment (undated) which I examined:

A pleat-fronted wrapper with front opening, hidden by the pleat. Its velvet has worn bare, so it probably got lots of use. Private collection.

It was a very small size, and had a tightly fitted underbodice that closed with hooks and eyes to the waist. It could have been worn with some of the hooks unfastened, but not as a maternal bust swelled.

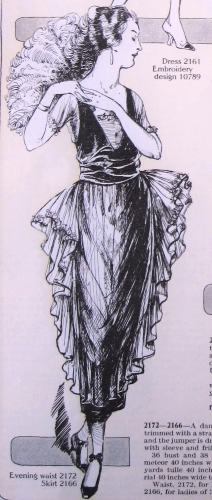

However, Empire-influenced fashions might be worn as aesthetic dress in the 1890s. This Tea dress is in the collection of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

The 1893 empire waist was just another fashion flame that flared briefly … and went out.